He who begins by loving Christianity better than Truth will proceed by loving his own sect or church better than Christianity, and end in loving himself better than all.

~ Samuel Taylor Coleridge

~ Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Do you trust God enough to seek His Truth even if it shatters what you have believed up to this day? If not, please do not bother to read further; this message is not for you.

The Princess and I have been studying Classical Latin and Koine Greek together and when I write this I mean that we work on the assignments, check each other's work, and quiz each other with flash cards. In this way she is learning another valuable lesson of life: all teachers are also students and all students are also teachers. The benefit for me personally is that I am learning these languages and not just relying on the answer booklet.

It was suggested in our Greek curriculum that we begin copying the New Testament in its original Greek text starting with the Book of John and I am considering copying the same from the Latin text since the entire Bible was translated into Latin also. Immediately, within the very first verse of John, I found that there is a good reason look deeper into the translation. Now just about every Christian has the first part of John memorized so it is easy to translate, but the very first verse of John is a point of great contention between the trinitarian and non-trinitarian believers.

Both ancient languages have their own specific syntax. Greek is much like modern English in that a sentence begins with a subject followed by the verb. If I have lost you, "Mary ran" is a subject-verb (action) example but "roses are flowers" is a subject-verb (state of being/copula) where the Greek order could be "flowers roses are" or even "roses flowers are." Latin is a bit more confusing as it places the most important word first, usually the subject of the sentence, and the verb is usually the last word of the sentence so it could literally read: David the lamb in the nothern field chased. (Think of Yoda in a Stars Wars movie and you get the picture. We can understand it, but the syntax seems backwards to us.)

In both Greek and Latin, there are noun declensions or the inflection of nouns, pronouns, adjectives, and articles to indicate singular and plural, nominative (subjective) case, genitive (possessive) case, gender, and so on. In both languages, the ending of a noun indicates its declension. Also, Latin has no articles at all, and Greek has no indefinite articles that would translate to be "a" or "an" but does have definite articles that would translate as "the."

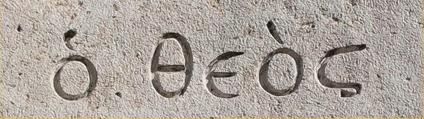

Now let's take a look at John 1:1 in its original Greek:

Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ Λόγος, καὶ ὁ Λόγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν Θεόν, καὶ Θεός ἦν ὁ Λόγος.

Yeah, it used to look Greek to me also, but I can read and understand it now. It might look a bit more familiar to you written with our alphabet (the capitalization is not in the original Koine Greek):

En archē ēn ho Lógos, kai ho Lógos ēn pros ton Theón, kai Theós ēn ho Lógos.

In most Bibles, the translations reads:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

However, being a new student of Greek, it seemed to me it should literally read:

In (the) beginning (there) was (existed) the Word, and the Word was (existed) with the God, and God was the Word.

Or without the capitals so that we can look at this objectively as it was in the original Greek text:

in (the) beginning (there) was (existed) the word, and the word was (existed) with the god, and god was the word.

I noticed that in the last phrase both "god" and "word" are in nominative case. This is why the last phrase is writtenΘεός ἦν ὁ Λόγος instead of Θεός ἦν ὁ Λόγον (notice the last letter in the last word). The predicate nominative seems interchangeable or at least as important as the subject in the translation to English, but which is the subject? Translating the phrase to the Word was God is probably not an error. However, the real point of contention between the trinitarian and non-trinitarian believers is mostly about the lack of an article and if an indefinite article should be inserted so that it would read the word was a god (or a deity).

If it had, left in its literal translation with its syntax so similar to modern English, would it make sense to place an article there?

in the beginning was the word, and the word was with the god, and a god was the word

or, another possible translation could be

in beginning was the word, and the word was with the god, and a deity was the word

But, if Θεόν is "god" in the previous portion of the sentence what is the change of mood that would it be "deity" in the latter or does it read differently if they both are "deity"?

in the beginning was the word, and the word was with the deity, and a deity was the word

I decided to look into this further because there are the unique nuances to any foreign language which more seasoned scholars would understand and there seem to be one that suggests it is proper to change the order. The absence of the article before Θεός could be meant to indicate that "god" is the predicate nominative of the phrase. Because Greek does not use word order quite the same as we do in English to indicate subject-object-predicate distinctions, there is ambiguity in a subject-predicate nominative construction. In such cases, the subject can be preceded with a definite article and the predicate nominative would have no definite article. I found this is called "Colwell's Rule" and it, too, is a point of controversy with non-trinitarian believers.

Yet, this rule is evident at 1 John 4:8:

ὁ Θεὸς ἀγάπηn ἐστίν which might seem to read "the god love is"

If "love" had a definite article, it would read "(the) love is god" but the definite article precedes "god" as in "(the) god is love." Its true meaning is a qualification of God rather than a deification of love.

Similarly, the absence of the article in John 1:1 may not indicate that Θεὸς is an indefinite noun as "a god," but that it is not the subject of the phrase. The absence of the article could assure the reader that "the Word" is the subject and that "God" is the predicate nominative of this phrase.

I have read about another argument in the use of Acts 28:6 that is translated as:

...But after they had waited a long time and had seen nothing unusual happen to him, they changed their minds and began to say that he was a god.

The Greek of that last phrase reads:

αὐτὸν εἶναι Θεόν

Certainly they would not mistake him for the God in this context and this translation of "a god" makes sense amidst of a polytheistic society where even great leaders were claimed to be gods. Also, notice that Θεόν in this phrase differs in that is also not in the subjective case but in the accusative case. Yes, different writers, but then comparing to the John 1:1, it comes to my mind that the author of John was specifically using the subjective case Θεὸς to make a point that it was God, subordinate to none, and not "a" god. Even authors today use improper grammar purposely to define a special point or make a phrase noticed and remembered.

There is also this from In the Salt Shaker

So, there are three ways to express the same translation of "God is spirit" without interjecting an indefinite article.

John 1:1..."the"... "a"... or no article--does it really matter? Apparently it does. The translation of this verse is one of the greatest rifts in Christian religions dividing those who believe in a Triune God and those who do not.

However, let us push all theology aside and think about this from viewpoint of the author (it may not have been John himself) and his writing style. If the author believed in one God, what purpose would it have served to write that anyone, even Jesus, was "a god"? It would only confuse people with a polytheistic viewpoint and it would be heresy if the Word (Jesus) was not God. I cannot see the logic in translating this phrase as anything but "the Word was God."

In the end it is not what I was taught by by men that forms my beliefs today, but what the Lord has shown and continues to show to me. He radiates Truth and I welcome Truth to be revealed to me, even if the knowledge would tear apart the foundations of what I have believed. Better to be in the Truth than to hold fast to that which is not from God. So I ask again: Do you trust God enough to seek His Truth even if it shatters what you have believed until now?

The Princess and I have been studying Classical Latin and Koine Greek together and when I write this I mean that we work on the assignments, check each other's work, and quiz each other with flash cards. In this way she is learning another valuable lesson of life: all teachers are also students and all students are also teachers. The benefit for me personally is that I am learning these languages and not just relying on the answer booklet.

It was suggested in our Greek curriculum that we begin copying the New Testament in its original Greek text starting with the Book of John and I am considering copying the same from the Latin text since the entire Bible was translated into Latin also. Immediately, within the very first verse of John, I found that there is a good reason look deeper into the translation. Now just about every Christian has the first part of John memorized so it is easy to translate, but the very first verse of John is a point of great contention between the trinitarian and non-trinitarian believers.

Both ancient languages have their own specific syntax. Greek is much like modern English in that a sentence begins with a subject followed by the verb. If I have lost you, "Mary ran" is a subject-verb (action) example but "roses are flowers" is a subject-verb (state of being/copula) where the Greek order could be "flowers roses are" or even "roses flowers are." Latin is a bit more confusing as it places the most important word first, usually the subject of the sentence, and the verb is usually the last word of the sentence so it could literally read: David the lamb in the nothern field chased. (Think of Yoda in a Stars Wars movie and you get the picture. We can understand it, but the syntax seems backwards to us.)

In both Greek and Latin, there are noun declensions or the inflection of nouns, pronouns, adjectives, and articles to indicate singular and plural, nominative (subjective) case, genitive (possessive) case, gender, and so on. In both languages, the ending of a noun indicates its declension. Also, Latin has no articles at all, and Greek has no indefinite articles that would translate to be "a" or "an" but does have definite articles that would translate as "the."

Now let's take a look at John 1:1 in its original Greek:

Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ Λόγος, καὶ ὁ Λόγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν Θεόν, καὶ Θεός ἦν ὁ Λόγος.

Yeah, it used to look Greek to me also, but I can read and understand it now. It might look a bit more familiar to you written with our alphabet (the capitalization is not in the original Koine Greek):

En archē ēn ho Lógos, kai ho Lógos ēn pros ton Theón, kai Theós ēn ho Lógos.

In most Bibles, the translations reads:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

However, being a new student of Greek, it seemed to me it should literally read:

In (the) beginning (there) was (existed) the Word, and the Word was (existed) with the God, and God was the Word.

Or without the capitals so that we can look at this objectively as it was in the original Greek text:

in (the) beginning (there) was (existed) the word, and the word was (existed) with the god, and god was the word.

I noticed that in the last phrase both "god" and "word" are in nominative case. This is why the last phrase is written

If it had, left in its literal translation with its syntax so similar to modern English, would it make sense to place an article there?

in the beginning was the word, and the word was with the god, and a god was the word

or, another possible translation could be

in beginning was the word, and the word was with the god, and a deity was the word

But, if Θεόν is "god" in the previous portion of the sentence what is the change of mood that would it be "deity" in the latter or does it read differently if they both are "deity"?

in the beginning was the word, and the word was with the deity, and a deity was the word

I decided to look into this further because there are the unique nuances to any foreign language which more seasoned scholars would understand and there seem to be one that suggests it is proper to change the order. The absence of the article before Θεός could be meant to indicate that "god" is the predicate nominative of the phrase. Because Greek does not use word order quite the same as we do in English to indicate subject-object-predicate distinctions, there is ambiguity in a subject-predicate nominative construction. In such cases, the subject can be preceded with a definite article and the predicate nominative would have no definite article. I found this is called "Colwell's Rule" and it, too, is a point of controversy with non-trinitarian believers.

Yet, this rule is evident at 1 John 4:8:

ὁ Θεὸς ἀγάπηn ἐστίν which might seem to read "the god love is"

If "love" had a definite article, it would read "(the) love is god" but the definite article precedes "god" as in "(the) god is love." Its true meaning is a qualification of God rather than a deification of love.

Similarly, the absence of the article in John 1:1 may not indicate that Θεὸς is an indefinite noun as "a god," but that it is not the subject of the phrase. The absence of the article could assure the reader that "the Word" is the subject and that "God" is the predicate nominative of this phrase.

I have read about another argument in the use of Acts 28:6 that is translated as:

...But after they had waited a long time and had seen nothing unusual happen to him, they changed their minds and began to say that he was a god.

The Greek of that last phrase reads:

αὐτὸν εἶναι Θεόν

Certainly they would not mistake him for the God in this context and this translation of "a god" makes sense amidst of a polytheistic society where even great leaders were claimed to be gods. Also, notice that Θεόν in this phrase differs in that is also not in the subjective case but in the accusative case. Yes, different writers, but then comparing to the John 1:1, it comes to my mind that the author of John was specifically using the subjective case Θεὸς to make a point that it was God, subordinate to none, and not "a" god. Even authors today use improper grammar purposely to define a special point or make a phrase noticed and remembered.

There is also this from In the Salt Shaker

- 1st Position: Article - Noun/Subject - Noun/Predicate

Here the construction must involve two nominative substantives, no modifier (like an adjective or participle). For one thing, an articular modifier is never placed in front of a noun it modifies. Then, if the anarthrous nominative is a modifier, this is an attributive position, not a predicate position. But, if both are substantives, the subject will be the one with an article, and the subject complement (put on the predicate side of the clause) will be anarthrous:

ὁ Θεὸς πνεῦμα ("God is spirit.") - 2nd Position: Predicate - Article - Noun/Subject

Here, the second term, the articular nominative, always must be a substantive (a noun, or something functioning as a noun). If it is an adjective, preceded by an anarthrous noun, this would be an attributive position, not a predicate position. If the articular nominative is a substantive, the anarthrous nominative in front of it can be either a substantive or a modifier (like an adjective or participle). The articular nominative substantive is usually the subject, while the anarthrous nominative in front of it is the subject complement:

πνεῦμα ὁ Θεός ("God is spirit.") - 3rd Position: Noun/Subject - Noun/Predicate

Here neither nominative will have an article. If one is a modifier and the other is a substantive, the modifier can be translated either as an attributive ("a good man") or as a subject complement ("a man is good"), depending on what seems to fit the context. But if both are nominative substantives, the first is usually translated as the subject, and the second as the subject complement:

Θεὸς πνεῦμα ("God is spirit.")

So, there are three ways to express the same translation of "God is spirit" without interjecting an indefinite article.

John 1:1..."the"... "a"... or no article--does it really matter? Apparently it does. The translation of this verse is one of the greatest rifts in Christian religions dividing those who believe in a Triune God and those who do not.

However, let us push all theology aside and think about this from viewpoint of the author (it may not have been John himself) and his writing style. If the author believed in one God, what purpose would it have served to write that anyone, even Jesus, was "a god"? It would only confuse people with a polytheistic viewpoint and it would be heresy if the Word (Jesus) was not God. I cannot see the logic in translating this phrase as anything but "the Word was God."

In the end it is not what I was taught by by men that forms my beliefs today, but what the Lord has shown and continues to show to me. He radiates Truth and I welcome Truth to be revealed to me, even if the knowledge would tear apart the foundations of what I have believed. Better to be in the Truth than to hold fast to that which is not from God. So I ask again: Do you trust God enough to seek His Truth even if it shatters what you have believed until now?

~ Lord, the more I learn, the more I question what I have learned. You are the only source of Truth. May I be ever open to hearing it and keeping it in my heart. ~